Background and Overview

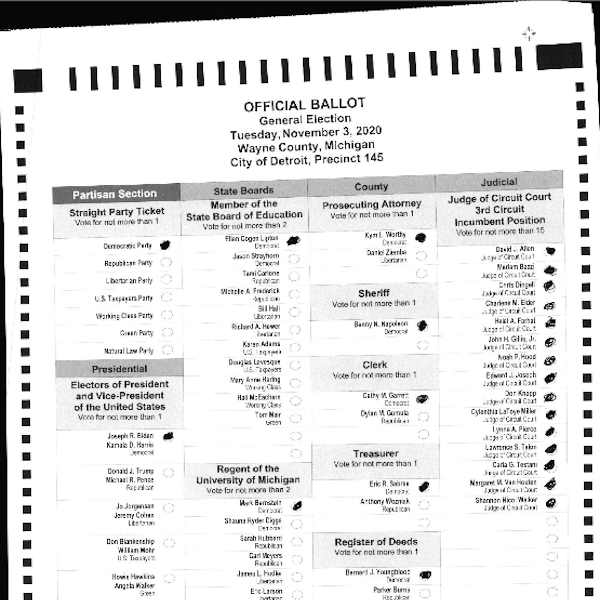

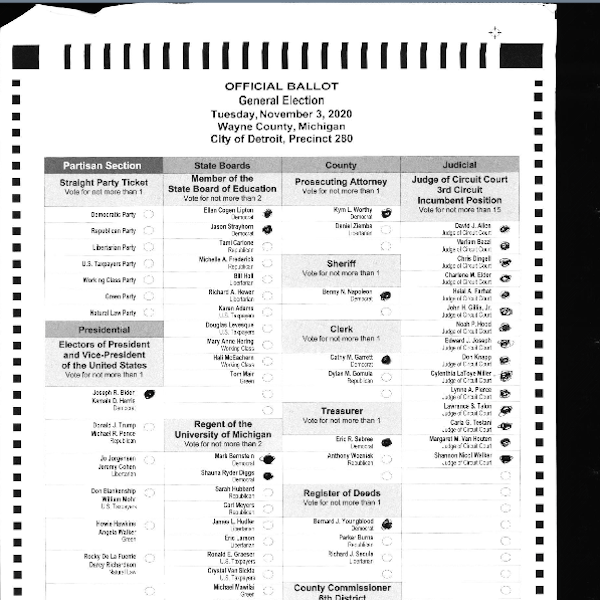

Following the 2020 Presidential Election in Detroit, Michigan, ballot images from in-person precinct voting were obtained through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request by Investigative Journalist, Yehuda Miller. The original digital images captured by tabulators during the election were not preserved, so election staff later re-scanned the physical paper ballots to produce these images. This independent analysis reviews those re-scanned images to assess ballot processing quality and readability, with the goal of verifying the integrity of the hand-marked precinct ballots.

The dataset consists of images from precinct-cast ballots (primarily hand-marked paper ballots voted on Election Day). Detroit saw high absentee voting in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, so precinct turnout was lower than absentee. The analysis focused on approximately 82,607 ballot images, of which the vast majority were traditional hand-marked ballots. Only about 113 ballots were produced by ballot-marking devices (BMDs), which print a human-readable ballot along with a QR code containing the vote data.

My custom optical mark recognition (OMR) algorithm successfully read over 99.88% of the hand-marked ballots (only 101 failures out of ~82,494 hand-marked images). This high success rate demonstrates both the effectiveness of the algorithm and the generally good quality of the re-scanned images, despite the challenges of post-election scanning.

Because these scans occurred after the election, there was no opportunity for real-time rejection of poor scans (as happens with normal tabulator scanning). Issues such as skewed placement, folded corners, or extraneous marks occasionally affected readability.

Unreadable Hand-Marked Ballots

Out of the hand-marked ballots, only 101 images could not be reliably processed. The primary causes were excessive rotation (skew) or large black borders introduced during scanning that exceeded the algorithm's tolerance thresholds. Rather than digitally altering the original images (e.g., deskewing or cropping), I preserved them in their received form to maintain authenticity.

Excessive rotation/skew

Large black border

Folded/missing corners

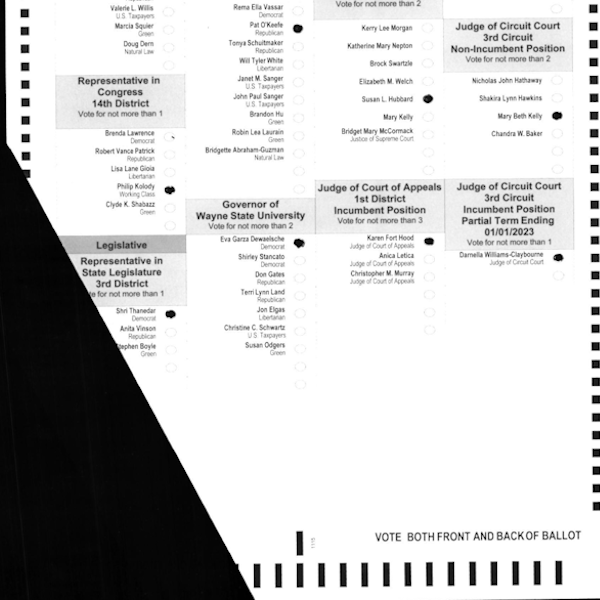

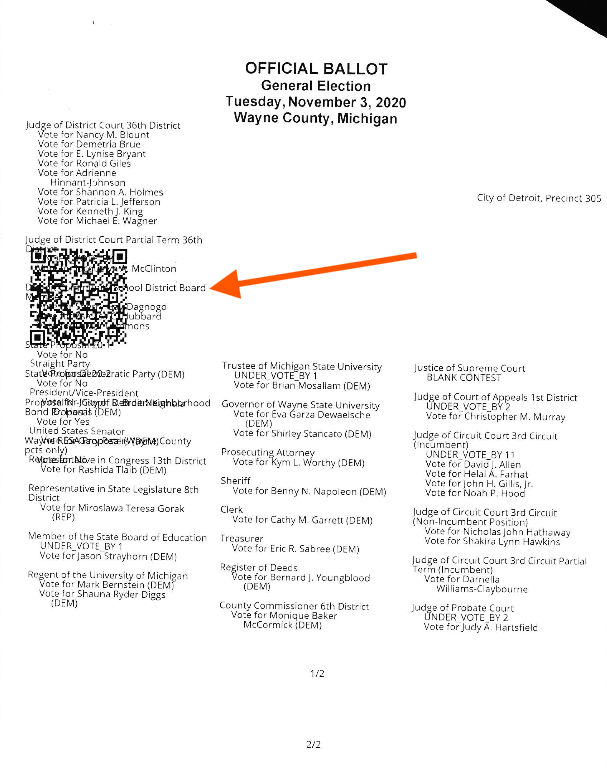

Ballot-Marking Device (BMD) Ballots

Approximately 113 ballots were printed by ballot-marking devices (BMDs) and contain machine-printed text with dense QR codes. These QR-coded ballots require different processing logic than traditional hand-marked ballots, so they were not run through the primary optical mark recognition algorithm. Given their small number (less than 0.2% of total precinct ballots), they have been set aside for potential future detailed analysis.

Several BMD ballots showed notable printing defects. In a few cases, text intended for the back side overprinted the front, partially or fully obscuring the QR code area. Such overprinting could have rendered the QR code unreadable by tabulators during the original election scanning.

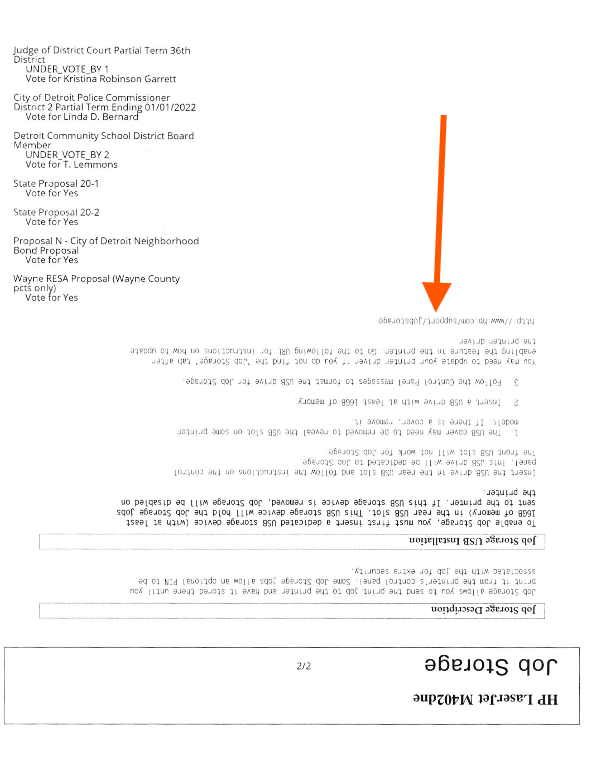

One particularly concerning example was a BMD ballot that had clearly been printed on previously used paper. Some sort of Windows printer log information was printed on the bottom of the ballot, showing that the paper had been used in a different context before being fed into the BMD printer. This indicates a serious lapse in ballot paper control: blank ballot stock was apparently not properly secured, allowing previously used printer paper to be reused as “blank” paper for the BMD printer. it highlights a flaw in chain-of-custody and material handling procedures that should not occur in a well-controlled election environment.

Overprinted text obscuring QR code

Overprinted text obscuring QR code

Scrap used paper used as a ballot

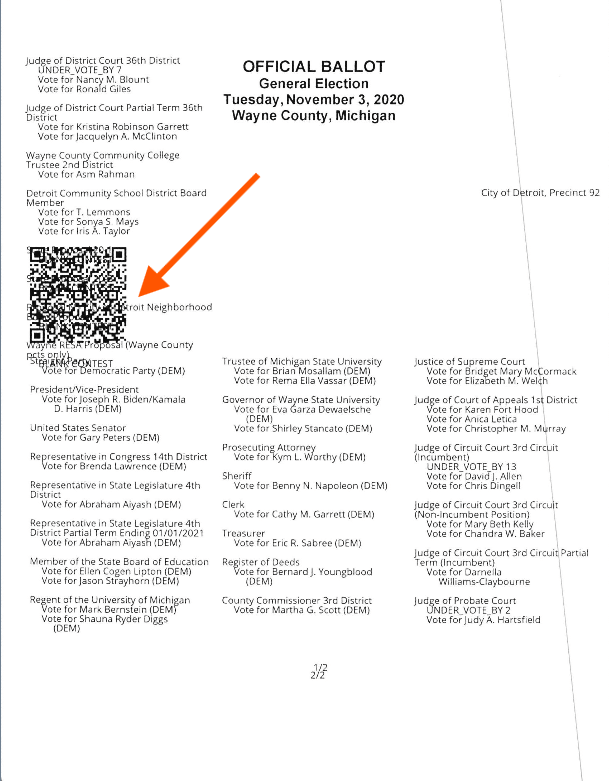

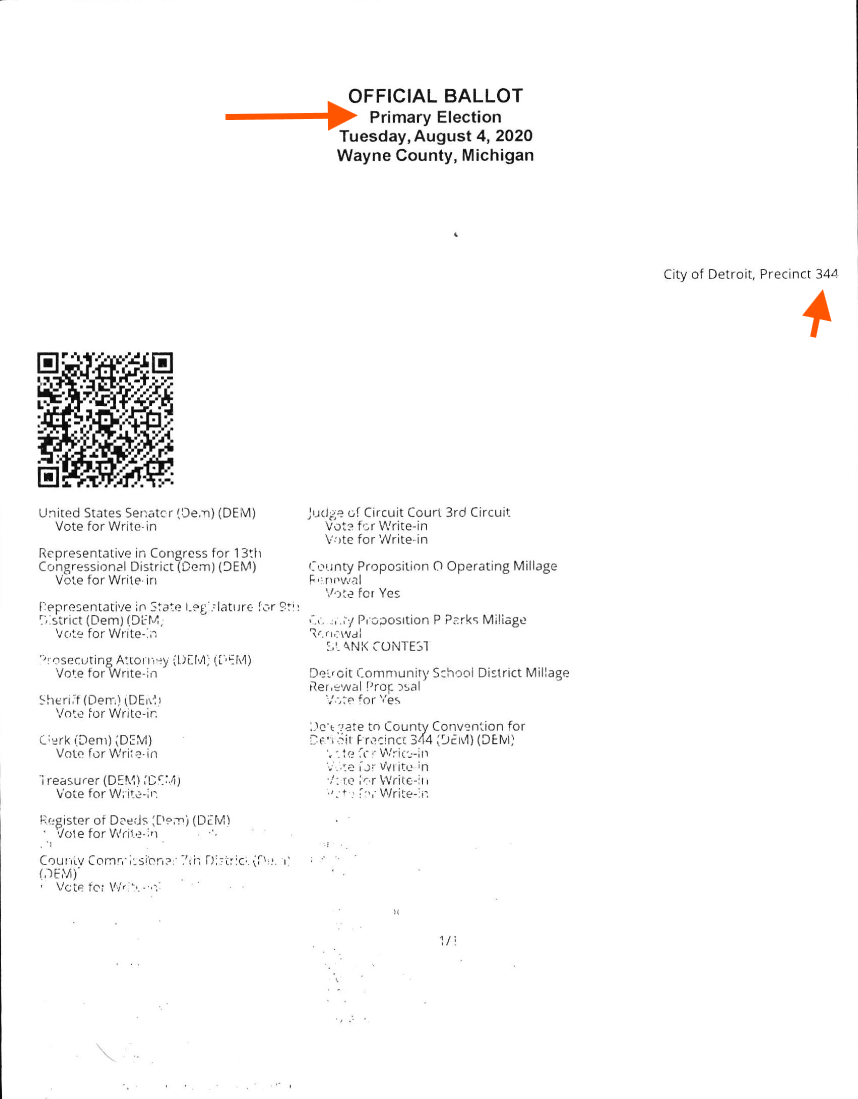

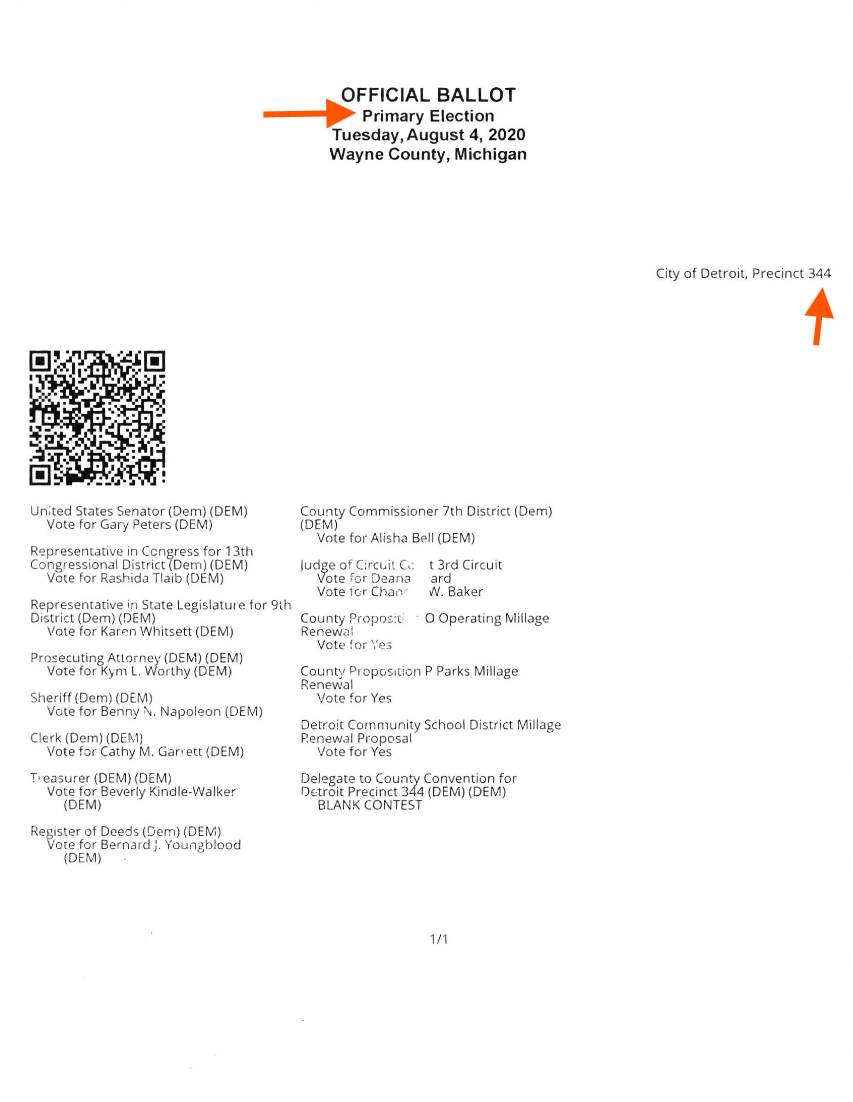

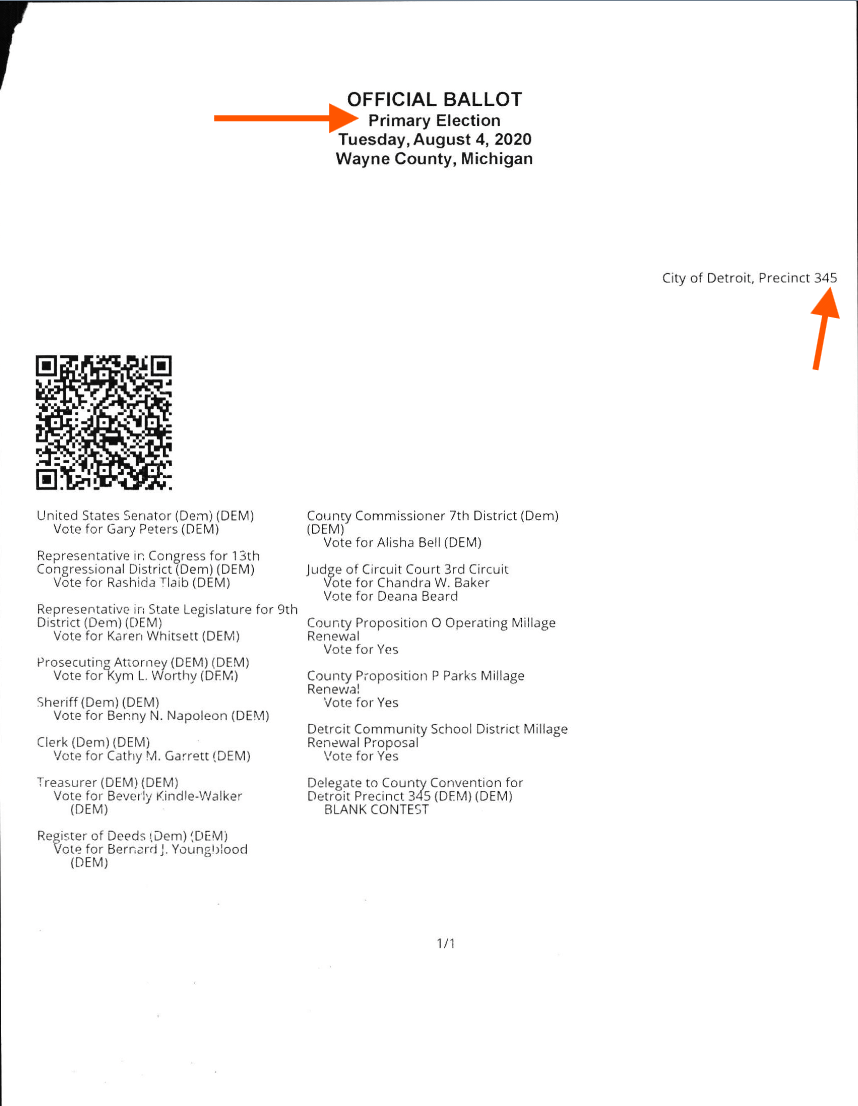

Misconfigured BMD Ballots? (Primary Election Style)

Three BMD ballots from precincts 344 and 345 appeared in general election batches but one displayed only blank write-in options for every contest—a layout consistent with a primary election ballot style rather than the November general election.

This anomaly most likely indicates that the ballot-marking devices in those precincts did not receive the updated general election programming and continued to use the primary election configuration. Fortunately, BMD usage across Detroit precincts was very low, so any impact on tabulated results would have been negligible.

An alternative, more concerning possibility is that the physical ballots scanned for these precincts (or some portion of them) were inadvertently from the earlier primary election rather than the general election. This would point to a mixing of ballot stocks during storage or retrieval prior to the post-election FOIA scanning process. Supporting this hypothesis, the image set also contained at least one hand-marked paper ballot clearly from the primary election (showing primary-specific contests). While the exact cause remains uncertain, either explanation—misconfigured equipment or commingled ballot stocks—reveals a procedural weakness that should not occur in a tightly controlled election environment.

Primary ballot used in general election

Primary ballot used in general election

Primary ballot used in general election

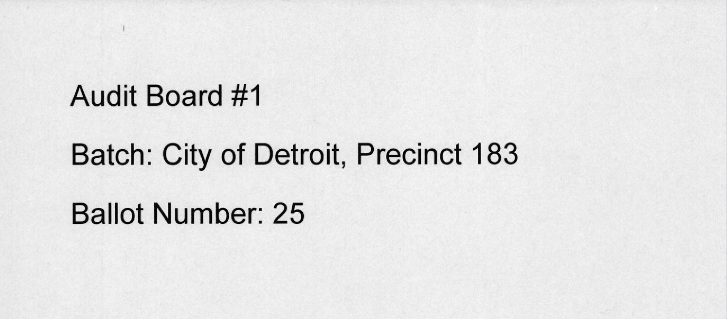

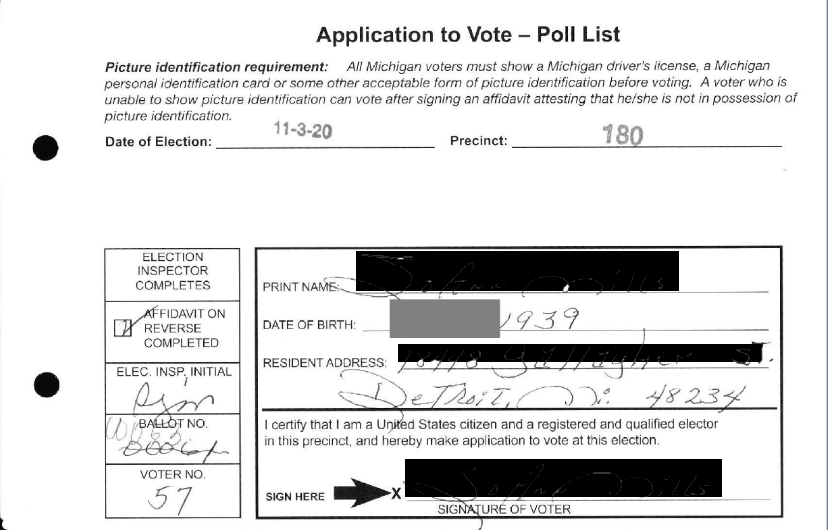

Non-Ballot Materials Included in Scans

Approximately 128 scanned items were not valid ballots. These included cover sheets, audit board placeholders, batch summary forms, and occasional voter applications mistakenly included in ballot bundles. Many were single-sided, causing minor issues in PDF-to-image conversion.

Common examples:

- Audit board placeholder sheets – likely used for duplicated or spoiled ballots.

- Wayne County Board of Canvassers batch cover sheets with tabulator details.

- "Application to Vote – Poll List" forms (voter registration-related).

- Handwritten notes (e.g., "No Write-ins but kicked out as write-ins").

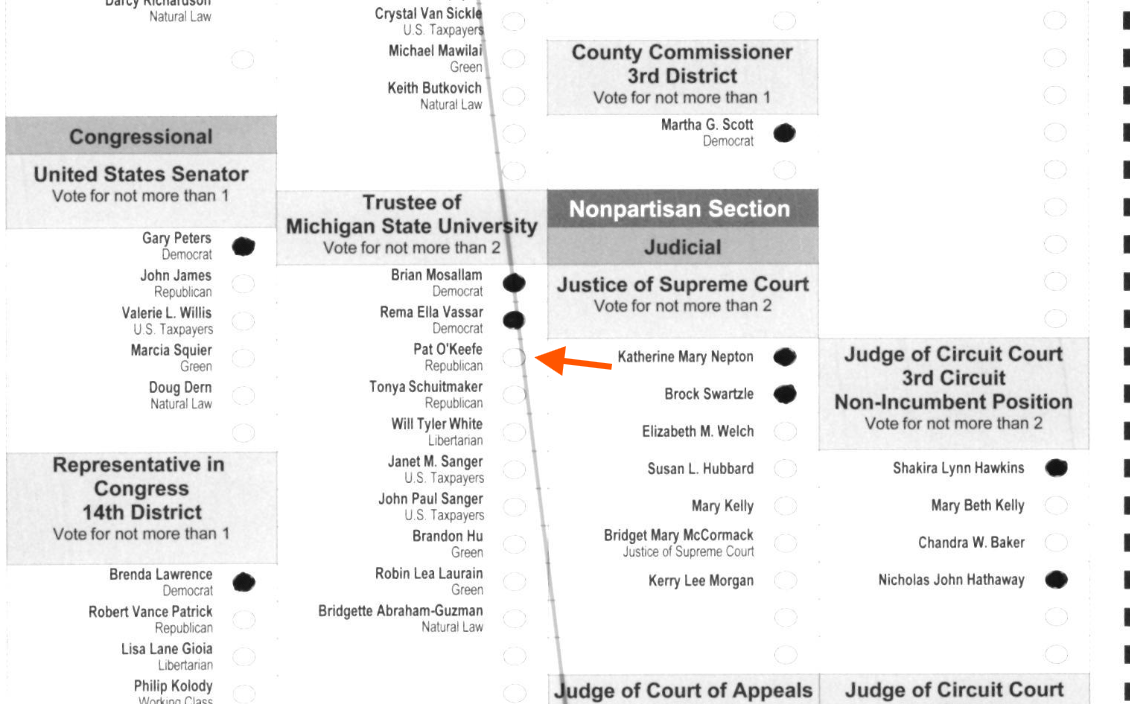

Scanner Artifacts: The Persistent Ruler

A prominent and recurring artifact appeared in many ballot images: an angled diagonal line resembling a ruler or measuring tool overlaid across the page. This line—likely caused by a calibration overlay, scanner bed mark, or misplaced physical ruler—varied in position, angle, and thickness across scans.

Contrary to initial observations, this ruler line frequently crossed directly over voting target ovals (the circles voters fill in). In numerous cases, it passed through or adjacent to contested races, causing my optical mark recognition algorithm to incorrectly detect overvotes, stray marks, or ambiguous voter intent. These false positives required manual review and correction to ensure accurate processing.

The artifact also occasionally overlapped the ballot-style barcode at the bottom of the page, though this rarely prevented successful decoding. While the overall impact was mitigated through post-processing checks, this unnecessary overlay significantly complicated automated analysis and reduced the reliability of untouched algorithmic results.

Recommendation: In any future post-election scanning of ballots—whether for audits, FOIA responses, or archival purposes—care should be taken to ensure scanner beds are clean and free of markings, and that no physical rulers or overlays are placed on or under ballots during scanning. Such artifacts introduce avoidable errors and undermine confidence in both automated and manual reviews.

Conclusion

Re-scanning tens of thousands of physical ballots after the election—using equipment not optimized for high-volume archival scanning—was a significant undertaking. Election staff worked under challenging circumstances and produced images of generally high quality. Minor issues—such as included non-ballot papers, scanner artifacts (including the persistent diagonal ruler line), occasional printing defects, and isolated cases of procedural lapses (e.g., reused paper stock and possible commingling of primary-election ballots)—were observed but did not prevent a comprehensive independent review of the precinct ballot images.

When comparing the vote totals derived from this independent processing of the ballot images against the official certified results, small discrepancies in raw counts are to be expected. Precinct in-person voting represented only a fraction of Detroit’s total ballots in 2020 (due to widespread absentee voting during the pandemic), and the image set included known non-ballot materials and scanning artifacts that required filtering.

A more exhaustive analysis could have further improved processing yields by applying targeted image corrections to the small subset of problematic ballots—such as digital rotation for upside-down or severely skewed images, cropping of excessive black borders, and removal of scanner overlays. With these relatively straightforward enhancements, nearly all of the hand-marked ballots could have been successfully interpreted automatically while still preserving the original images for verification.

Overall, the ability to independently process and analyze this large collection of precinct ballot images provides valuable transparency into the 2020 Presidential Election results in Detroit, Michigan.

English

English